Neil Thompson (1996) includes “talking” as an important step in critical reflection. By sharing their understanding of the learning experience with others, students are forced to articulate their learning in a way that a general audience can understand. Based on their own testimonials, students are excited to share their experience and are often surprised that they learn more just from talking about it.

Haynes (2007) describes the Experiential Learning process as a 5 step process:

- Experiencing/Exploring “Doing”

- Sharing/Reflection “What Happened?”

- Processing/Analyzing “What’s Important?”

- Generalizing “So What?”

- Application “Now What?”

In this expansion of the DEAL model, students share their results, reactions, and observations with their peers as part of the second step in the process. Student discussion and presentation becomes a means of revealing their learning, both to themselves and others. Using peer evaluations and a survey, Girard, et al (2011) found that “the majority of students agreed or strongly agreed (combined) that presentations contributed to their learning of class materials (79.8%), developed listening skills for key points (62.5%), brought different perspectives for class learning (84.6%), and improved public speaking skills (89.9%).”

As with all reflection methods, it is the process, not the final product, which transforms the experience into learning. Through the public presentation of their learning, students encounter live feedback from a varied audience. The give and take which can occur in a conversation when explaining a poster or in a post-presentation gathering allows the spontaneous, unexpected learning which comes from personal engagement.

Applicability: Reflective presentations are particularly appropriate for culminating experiences and individual research projects. Since a participatory audience expands the student’s learning opportunities from the presentation, presenting to peers or faculty who have similar scholarly or experiential foundations is valuable. Sharing reflections do not need to be grand summaries of a project. Simple, one on one sharing where students verbally respond to prepared reflection questions allows a spontaneous element often edited out of written reflection answers.

Sample assignments:

Experiential Learning at the University of Puget Sound used the three-minute thesis format (http://threeminutethesis.org/) to promote the transformative power of EL activities. Students from a broad array of experiences each addressed the fundamental question: What was transformative about the experience? The talks needed to include a description of the EL opportunity, the student’s own experience of it, reflection upon the learning outcomes, and the explicit benefits of reflection in their individual learning.

Whitman College’s Undergraduate Conference allows students from across the college to share their research and creative projects in a single day during spring semester. All students are encouraged to attend multiple presentations, so classes are cancelled. The conference is noteworthy for its variety of presentations, from oral and poster presentations to musical performances to special exhibitions. (https://www.whitman.edu/academics/signature-programs/whitman-undergraduate-conference/guidelines-for-presenters/general-guidelines-and-instructions)

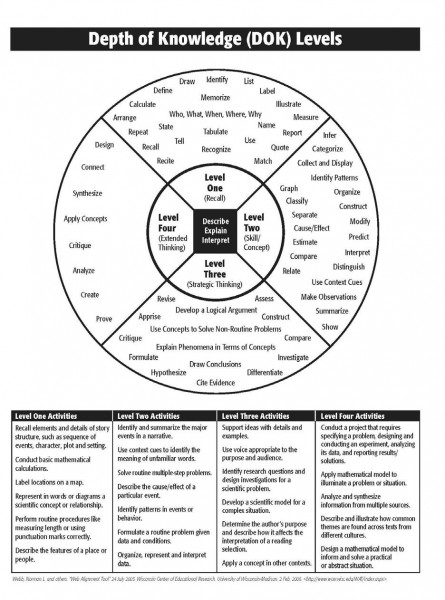

An example of a simple paired sharing comes from Halcrow (2014). Ask students a question from the Depth of Knowledge Levels Wheel (Diagram 7). Give students time to think about the question on their own; then ask them to pair with a partner to discuss the idea. Finally, have each partner group share their findings/thoughts with the class. Discuss.

(reproduced from https://static.pdesas.org/content/documents/M1-Slide_19_DOK_Wheel_Slide.pdf)

Diagram 7

Sample Assessment:

Presentation assessment rubrics must consider content, style, and communication effectiveness. David Walbert (2011) identifies six features of effective presentations and an associated grading rubric (http://www.learnnc.org/lp/pages/647).

- Focus

- Organization

- Support and Elaboration

- Style

- Conventions

- Presentation Skills

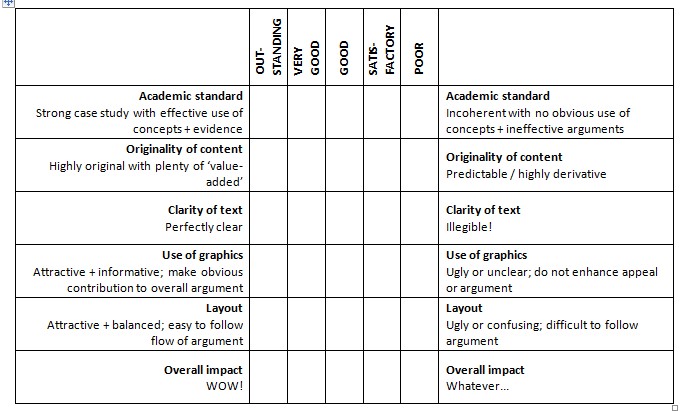

Nick Spedding, University of Aberdeen, created a combination of faculty and peer assessment for poster presentations. The peer form follows in Diagram 8.

(reproduced from https://www.abdn.ac.uk/cad/documents/TF_Events/N.Spedding_TF_Event_2013.pptx.)

Diagram 8

References

Girard, Tulay, Musa Pinar, and Paul Trapp. (2011). An Exploratory Study of Class Presentations and Peer Evaluations: Do Students Perceive the Benefits? Academy of Educational Leadership Journal. 15(1). 77-94.

Halcrow, Katie. (2014). Reflection Activities: Service-learning’s not-so-secret weapon”. Civic Leadership Initiative. http://mncampuscompact.org/clio/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2014/07/Reflection-Activities-for-All-Classrooms.pdf

Haynes, C. (2007). Experiential learning: Learning by doing. http://adulteducation.wikibook.us/index.php?title=Experiential_Learning_- _Learning by Doing.

Instructional Strategies: Experiential Learning. Instructional Guide for University Faculty and Teaching Assistants. Northern Illinois University. http://www.niu.edu/facdev/resources/guide/

Spedding, Nick. (2013) “Poster + Peer Assessment - GG2509: Environment and Society.” Powerpoint presentation. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/cad/documents/TF_Events/N.Spedding_TF_Event_2013.pptx

Thompson, Neil. (1996) People Skills. London: Palgrave.

Walbert, David (2011). “Evaluating Multi-media Presentations”. LEARN NC: K-12 Teaching and Learning. The UNC School of Education.