Many egg-laying animals lack parental care and instead leave eggs unattended and exposed to environmental pathogens that can cause egg mortality. We are interested in mechanisms that animals use to prevent egg loss in the absence of parental care, and propose a novel source of protection: protective microbes that passively transfer from the reproductive system of the mother to eggshell surfaces during egg-laying.

In collaboration with Dr. Mark Martin and& Dr. Betsy Arnold at the University of Arizona, we study the maternal and eggshell microbiome and their interactions with soil pathogens utilizing lizards as a model system.

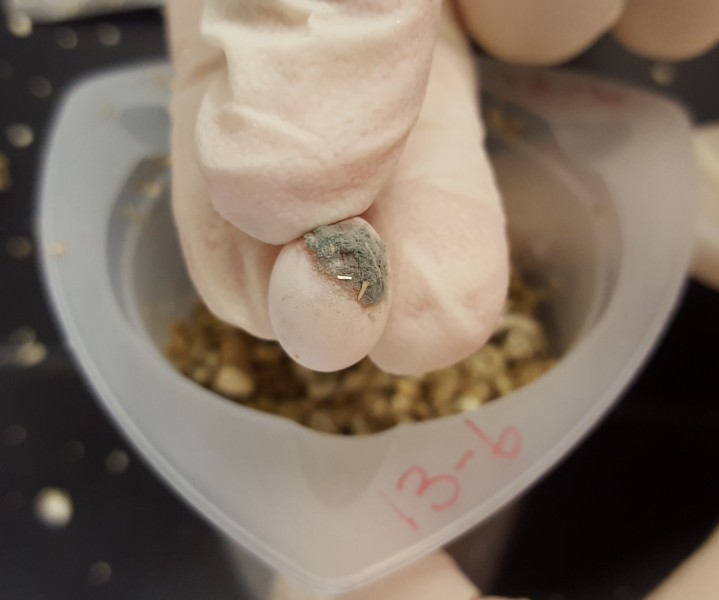

Preliminary data from the striped plateau lizard (Sceloporus virgatus) suggest that mature eggs have more bacteria, less fungal growth, and higher hatch success when oviposited than when surgically removed without cloacal contact (Science News published a brief story about these data). With support from NSF, we will:

- quantify temporal variation in cloacal microbiomes of S. virgatus to test whether females’ microbiota change in preparation for egg-laying;

- use both experiments and observational study to characterize vertical transmission and the role of transmitted microbes in reducing egg infections;

- relate cloacal microbiota to female reproductive success, signals/cues of reproductive value (such as the female ornament and skin lipid chemical cues), and behavioral interactions; and

- conduct comparative studies across Sceloporus spp. to examine the relationship of reproductive mode (oviparous vs. viviparous) and infection risk on antifungal capacity of cloacal microbiota. Vertical transmission during oviposition is expected to be a general phenomenon, so results should be broadly applicable to other oviparous taxa.

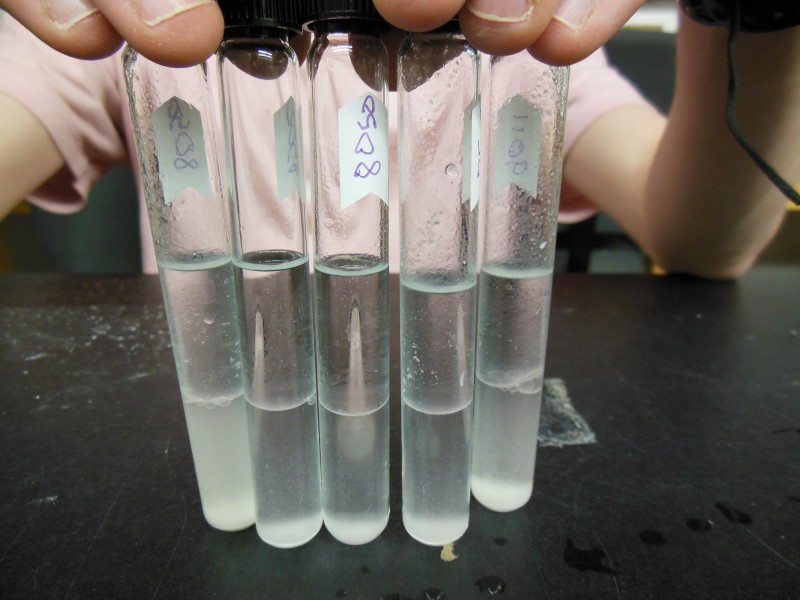

This work involves next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics analyses, culture-based techniques, in vitro analyses, and field study. We hope our research will be foundational to the integration of microbiology and behavioral ecology, contributing to long-standing theoretical questions about costs and benefits of parental care (or lack thereof) and sexual signaling, expanding knowledge of microbial diversity and composition in an understudied host lineage, and potentially identifying new antifungal agents.