A park project in Tacoma empowered underserved kids and gave them a safe place to play. When one of those kids turned up at Puget Sound a decade later, he showed that human connection is stronger than the lines that divide us.

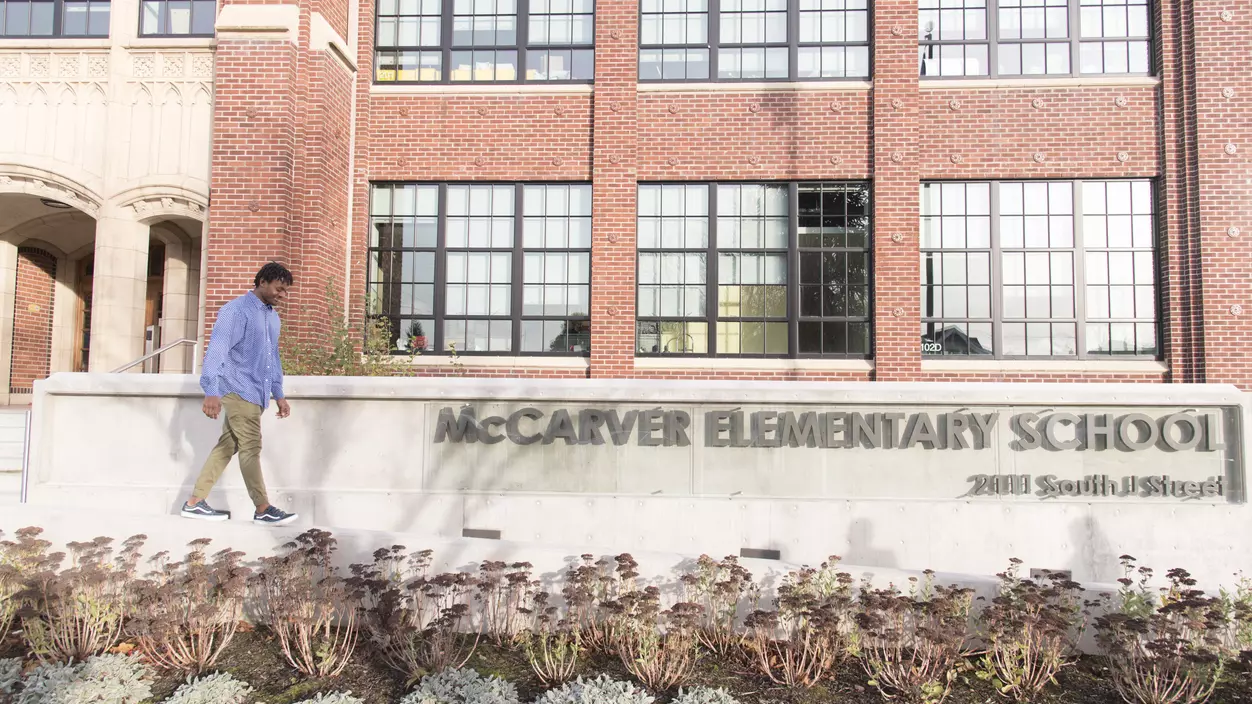

It was Mushawn’s idea to build the garden. He was proud of that. His fifth-grade class had been invited to help design the empty park next to their school, and while the other kids were dreaming up slides and swing sets, spray grounds to run through on hot summer days, monkey bars and mosaic tiles, Mushawn Knowles ’20 told the landscape architecture students who were creating the park model that he wanted to feed the homeless and hungry.

This was not an abstraction for a kid growing up in the Hilltop, Tacoma’s most underserved neighborhood—Mushawn had neighbors and friends in mind. So when he saw the garden sketched into the design plans for McCarver Park, it was a turning point for him. “I saw that I had a purpose, something that was bigger than me,” he says now, nine years later. “When I saw my idea manifest—that was empowering.”

That’s because the Zina Linnik Project, a initiative to revitalize two city parks that flank the Hilltop, was not an ordinary urban development project. It began as a memorial to Zina Linnik, a 12-year-old from the neighborhood who was kidnapped and murdered in 2007, and expanded into a larger campaign run by Greater Metro Parks Foundation to create safe spaces for children to play.

The innovative factor was that fifth-graders at McCarver Elementary took the lead in design, fundraising, and advocacy. They were assisted by community members, including students and faculty at the University of Puget Sound. In the process, the kids discovered that their voices held power, and they were able to imagine futures for themselves beyond their current context.

That’s what happened for Mushawn. He became a focused student and a leader in his class. He wrote speeches and delivered them in front of the city council and legislators at the state capitol. And as he found mentors in the college students and their teachers who came to help, Mushawn started thinking about college for the first time. The path that he ultimately created for himself led to the University of Puget Sound, where he is now a sophomore.