Lael and Cait named the bike mentorship program Anchorage GRIT (Girls Riding Into Tomorrow). While pedaling together along a 1,700-mile tour down through Baja, Mexico, the pair had imagined what they would have wanted to do when they were in middle school, that time when you’re sandwiched between childhood and adulthood, between aspirations and anxieties, between the world of play and the increasing awareness of the realities of life.

The goal of the six-week program was to get the girls riding safely and confidently around the city. Beyond that, Lael and Cait wanted to help the girls feel empowered to dream up their own adventures and make them happen. Participants came from Anchorage’s largest middle school, a low-income Title I school where a diverse student body speaks some 96 different languages, and from a magnet school that attracts kids from all over the city.

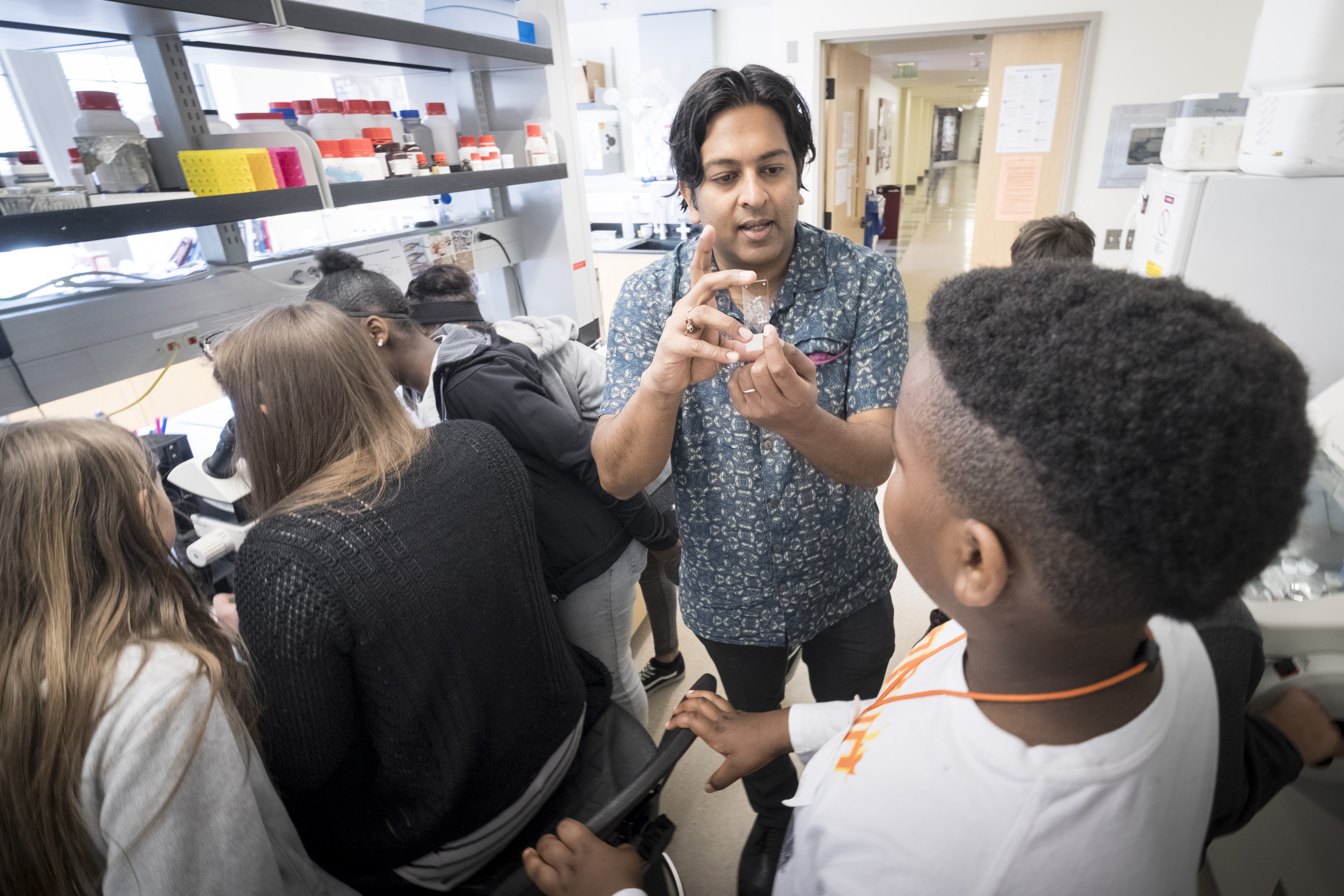

With corporate sponsorship and a little bit of fundraising, GRIT outfitted the girls with their own bicycles and helmets that they’d be able to keep after the program ended. The group met two or three times each week for rides and special sessions on biking safety, bike maintenance, navigation, mountain biking, and stretching taught by a cadre of women experts, including an Olympic Nordic skier and a representative from a local cycling equipment company who helped the girls make their own bike bags. These women served as additional mentors, helping the girls see opportunities they’ll have as they grow up.

Through short rides and workshops after school, and longer rides on weekends, the girls learned how to negotiate weather, traffic, and routes that took them between trails and roads. They learned how to grease their chains and change a tire. And they made new friends, with girls who might never have crossed their paths otherwise.

Lael doesn’t stand like a champion. She hunches her lithe, 5-foot-7-inch frame slightly, in a typical getup of jeans, a T-shirt and Birkenstocks. Her short, chestnut hair flips over to the side, sometimes covering one of her eyes, which are blue as a noonday sky. “Ha!” she’ll often crack at the end of a sentence, chuckling at what she just said.

In GRIT, Lael is less a teacher than a fellow rider. She leads through enthusiasm, through friendship. “Lael is about one of the coolest women I’ve brought into my daughter’s life,” Joanne Parent, mother of one of the GRIT girls, said. “She believed in all the girls.”

Less than a month into the program, nearly half the bikes were stolen from a storage unit outside one of the schools. The girls were devastated. Lael cried.

Clearly, GRIT lessons went well beyond bicycles. “They got to see that sometimes things don’t work out, and that’s OK,” Lael said.

But Lael is the kind of person who looks at a water bottle as half full. “We’re not going to stop,” she thought. That afternoon, the bikeless girls walked to their GRIT meeting a mile away. And when word got out about the theft, people in Anchorage responded. Within a day, they’d raised $10,000 and had gotten offers from strangers to buy bikes for the girls. They replaced the bikes and still had a nest egg to expand GRIT the following spring. Lael and Cait plan to share the program with communities across Alaska to get as many girls out riding as possible.

A buzzword these days among parents, teachers, coaches, and CEOs, “grit” refers to a quality of perseverance, of stick-to-itiveness for reaching big goals. When it comes to success, researchers say, grit may be as important as talent and opportunity—maybe even more so.

When Lael is riding hard, she falls, she cries, she bleeds. “If I set out to do this,” Lael says about times when things get tough, “I’m going to finish.” Grit is about riding even when you think you can’t. It has nothing to do with not falling, and everything to do with getting back up again.

Among the GRIT girls, Natalie Buttner was notorious for falling. She fell when her bike hit ice, and she fell when it hit snow. She fell going uphill and going downhill.

Natalie had moved to Alaska from Connecticut a few months before GRIT started. She was nervous that first day in her new school. It felt so much bigger than her old one, where she’d left behind friends she’d known for years. And in the GRIT program, everyone seemed to be riding faster—and better—than Natalie.

“Falling is part of riding,” Lael explained to the girls. This champion cyclist has fallen off her own bike too many times to count. She flew tail over teakettle—an “endo” in cyclese—over her handlebars while riding in Baja when she hit a patch of sand at the bottom of a steep drop. The fall knocked her out and fractured a vertebra, but she was low on water so she kept riding to the next town. On an Anchorage route last spring, she slipped while pedaling across a narrow bridge and cracked two ribs. A week later she was rolling side by side with the GRIT girls on their culmination ride.

On the last day of the program, after Natalie had made the huge climb for the final night at the cabin, where the girls spent hours telling stories, laughing, and playing games, she fell on the ride back out to meet up with the parents. She slid 15 feet down a steep bank along the trail and was covered in sand. The impact broke off one of her brake levers. Grit filled her mouth. Her long blond hair splayed around her, Natalie lay on the dirt looking up at the concerned, helmeted faces above her. They were like a canopy of trees, with the huge, bright Alaskan sky behind them. Then she did just what Lael had shown her how to do. She got up and kept riding.

Miranda Weiss is a science and nature writer living in Homer, Alaska. Her natural history memoir, Tide, Feather, Snow: A Life in Alaska, was a best-seller in the Pacific Northwest. She has a biology degree from Brown University and an M.F.A. from Columbia University. Her writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Scholar, Alaska magazine, and elsewhere.