Reflections on personal narrative as a means of resistance

“Stories matter. Stories are a reflection of power.” When Alicia Garza, a founder of the Black Lives Matter movement, said this during her keynote address at the close of the 2018 Race & Pedagogy National Conference held on campus last September, it struck me that this was the crux of the conference. Its title,“Radically Re-Imagining the Project of Justice: Narratives of Rupture, Resilience, and Liberation,” was a call for participants to share their stories and to speak into the spaces that have rendered them invisible.

I recognized the power of this narrative framework, viewed through the lens of my work in black feminist rhetorics. From Harriet Jacobs penning her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, while in hiding to Audre Lorde’s biomythography Zami: A New Spelling of My Name to the release of Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade, black women have historically deployed storytelling as a means of liberation and subversion. Being able to tell our own stories in our voices, despite all efforts to silence and erase us, is central to the black feminist intellectual tradition.

Black queer feminist poet and essayist Audre Lorde encouraged women to tell their own stories because silence would not protect them. In her groundbreaking essay, “The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action,” she challenged readers to consider all the ways they silence themselves, and asked them to resist that silencing: “What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?”

The stories of the silenced and erased were center stage at the conference. Presentations about the experiences of indigenous people, immigrant communities, and the work of scholars, activists, artists, and community organizers across the country illuminated that we are in a collective fight for liberation and that storytelling is an essential part of that work.

Audre Lorde argued that people must use their voices as a means of resistance: “But for every real word spoken, for every attempt I had ever made to speak those truths for which I am still seeking, I had made contact with other women while we examined the words to fit a world in which we all believed, bridging our differences. And it was the concern and caring of all those women [that] gave me strength and enabled me to scrutinize the essentials of my living.”

She credited her ability to tell her story to the women in her life. Working within and for a community is what drives black feminist thinking, and that ethos was prominent in the work of the organizers of the conference and those who presented their ideas. This work is intersectional in nature.

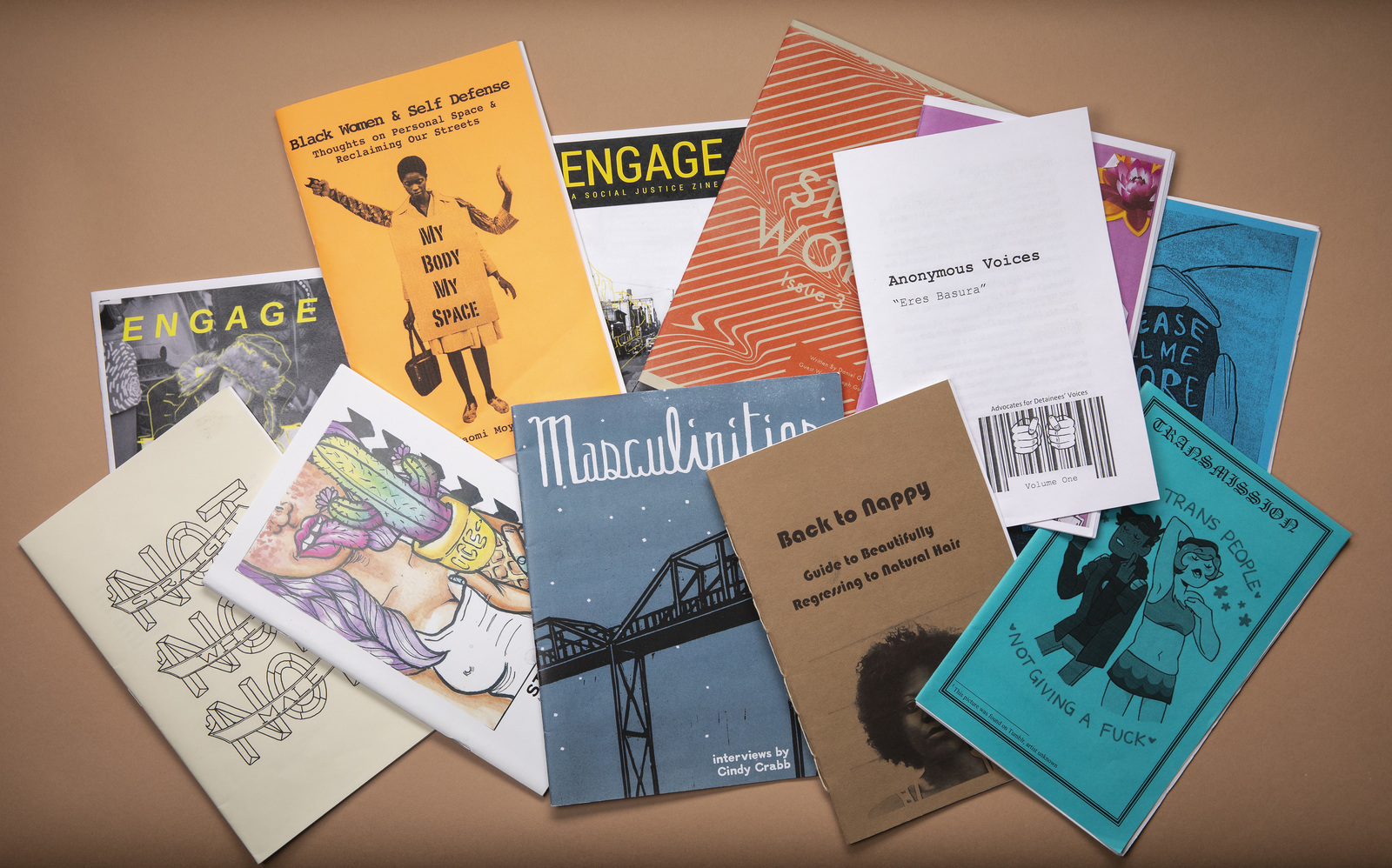

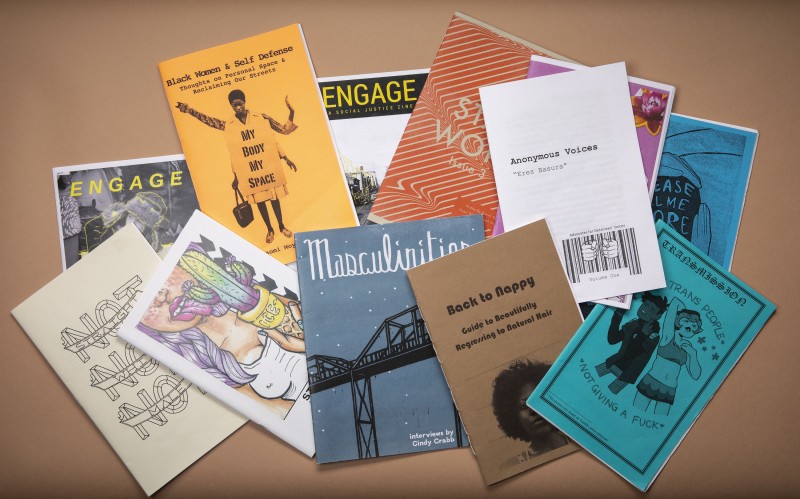

At Puget Sound, I teach a course on zines, using the Collins Memorial Library zine collection, and I ask my students to consider the ways that zine-makers use their stories to disrupt, challenge, and push back against power. Zine-makers are typically members of marginalized groups, and they use handmade, photocopied zines as a way to assert their voices in the public sphere. By studying this raw, unfiltered work, my students and I are able to learn from people who may not have a voice in academic spaces.

I gave a presentation on zine-making at the conference as part of the larger campuswide community conversation about race and education. Other panelists were speaking on similar topics, such as teaching English composition using music, spoken-word poetry, and comics. These methods allow those who belong to marginalized identity groups, whose voices are often silenced and histories corrupted, to narrate their own experiences.

My zine presentation co-panelist and student Rose Pytte ’18 shared a zine from Advocates for Detained Voices. The collective goal of this student-run organization is to make visible the experience of people rendered invisible by state power and systemic inequality, and the zine illustrates the detainees’ struggles. The act of sharing their stories outside of the confines of the detention center gives those who have been rendered powerless control over their own narratives.

Educational spaces, particularly universities, can be sites of oppression or sites of liberation. A liberal arts model asks educators to make space for alternative ways of knowing and being, by creating curricula, writing syllabi, and composing assignments that serve to dismantle rather than uphold systems of power and oppression that serve some students and marginalize others. Teaching with the zine collection demonstrates for my students that telling your story can be a liberating practice that is an essential part of our collective work on campus and an exercise in considering whose stories are worth preserving and whose stories are considered valuable.

Hypervisible invisibility is a profound experience of black womanhood. As Audre Lorde reminds us, “Within this country where racial difference creates a constant, if unspoken, distortion of vision, black women have on one hand always been highly visible, and so, on the other hand, have been rendered invisible through the depersonalization of racism.” When black women reclaim their stories, they counter this “distortion of vision.” The work of telling black women’s stories—and forcing society to contend with black women’s narratives rather than ignoring them—is an act of disruption that aims to transform our world.

“Stories matter,” Alicia Garza said. As a brand-new faculty member at Puget Sound, I have often wondered what kind of story I have to tell. Where do I fit into the narrative of this place? As I attended the conference and spoke to educators from across the country, I began to feel myself becoming part of a story about being a black woman on this campus, following the lead of those who came before me and joining the handful of us here now doing the work of reframing the narrative.

The beauty of the Race & Pedagogy National Conference was that it brought educators, artists, and activists together to reimagine the ways we can disrupt the status quo and tell new stories of resilience. It left attendees hopeful, inspired, and ready to continue telling stories that matter.