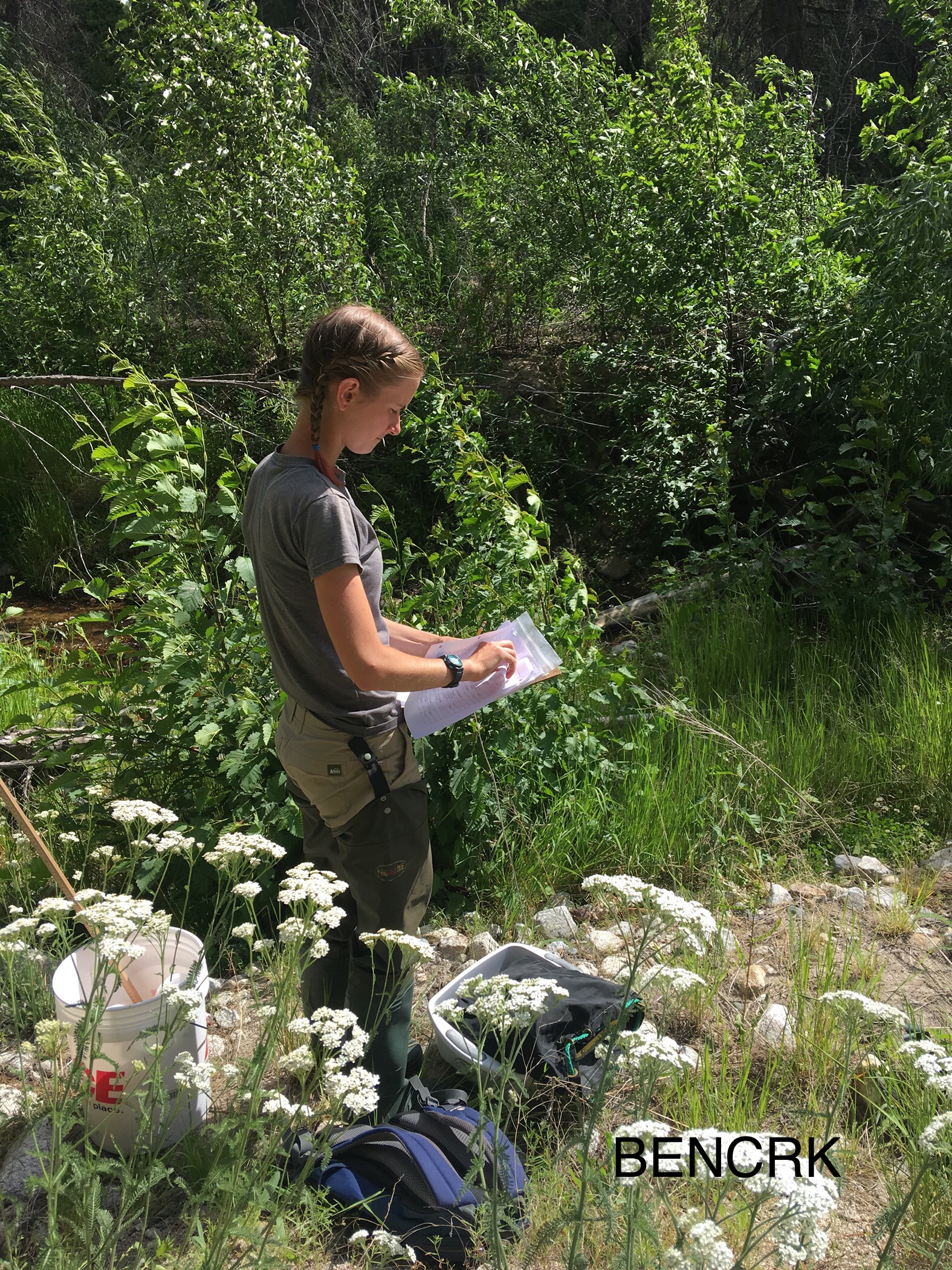

With the gaping mile-wide crater and expansive pumice plain left by Mount St. Helens’ violent 1980 eruption as a backdrop, Alex Barnes ’20 balances on a floating log with a razor blade in one hand and a test tube in the other. He’s in the middle of Spirit Lake, on a manmade log raft gathering samples for his summer research project.

Known for the thousands of logs that float on its surface as a reminder of the eruption’s destruction, Spirit Lake received the full force of Mount St. Helens’ blast. Not only trees but ash and debris crashed into the lake, and volcanic gases seeped from the lakebed, turning the once pristine Spirit Lake into a toxic pond void of oxygen and life. But the lake is recovering, and today it provides a rare opportunity for scientists like Alex to study the restoration of a lake severely impacted by a major volcanic eruption. Alex is part of a team of local researchers working on a project to gather data about the insects, bacteria, and plankton living in the lake and on the logs.