Research led by Phillip Morin ’86 suggests that the killer whale might be at least three separate species.

The sign-off on Phillip A. Morin’s emails contains a renowned Albert Einstein quote: “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.” The quote fell short in describing Einstein. And it doesn’t describe Phil Morin ’86 in his entirety, either.

Morin, a conservation geneticist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has worked with the famed primatologist Jane Goodall and has built a career helping the world better understand killer whales. He’s certainly passionately curious. But he has almost four decades of expertise to back up that curiosity.

Now, his research has concluded that some of those killer whales, or orcas, should be considered separate species. The results, published this March in the journal Royal Society Open Science, could be a game-changer—and could increase opportunities for whale conservation.

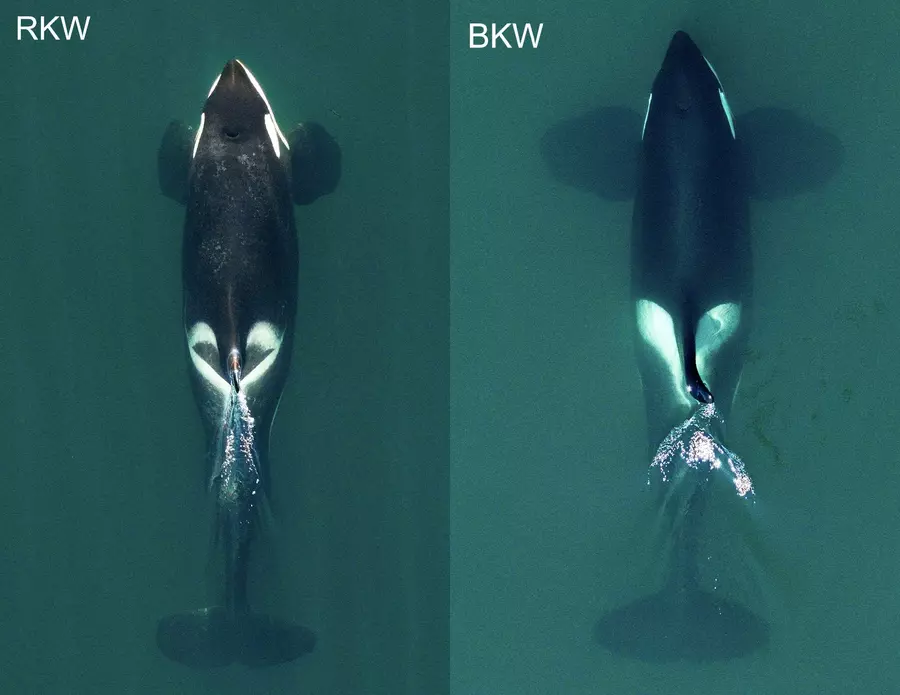

Evolution doesn’t always conveniently provide bright lines between species; there isn’t even a single global standard for how “species” is defined. Within the world of killer whales exist numerous varieties, called ecotypes. Morin and his colleagues focused on two ecotypes that roam the North Pacific—Bigg’s killer whales and resident killer whales—to learn whether the differences between them are just regional variations, or are enough to consider them separate species.

Unfortunately for researchers, killer whales resist being watched. They move around a lot and are hard to get close to—and, well, they’re also usually underwater.

A key to the latest research effort was genetics, made possible by the decades-long accumulation of small skin samples, collected using dart biopsy from live animals and dead beach-stranded animals, as well as DNA from the teeth and bones of museum specimens.