Abby Williams Hill is best known for painting landscapes of the American West in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Now, more than a century later, her writings reveal a more complicated picture of what she saw.

The tourists at Yellowstone National Park on that September day in 1905 gaped at Abby Williams Hill. The artist was a sight: her hands caked with dirt, her face studded with gnat bites, a worn dress soiled by another day of painting and tromping with her four children through the wilds. Hill didn’t look like anybody’s idea of a proper lady. She didn’t act like one, either, taking her kids out on adventures, one nomadic day after another for months on end, while her husband stayed home back in Tacoma.

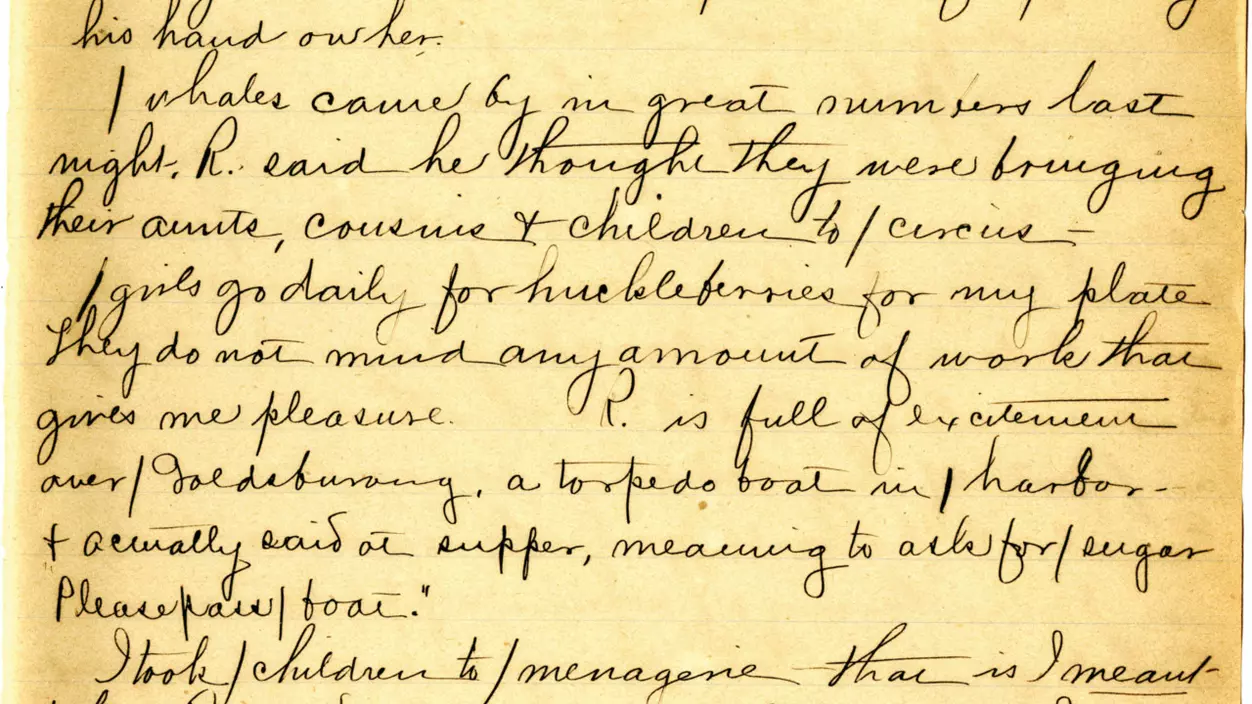

At her campsite later that evening, Hill dipped her pen into an inkwell to document the encounter in a diary entry.

"They took a long look at me... Just then an addition to the party arrived and to her all was explained that I was an artist and these my children and they always went with me.

She exclaimed in horror, “[And] do you take these children way off like this? Suppose they got sick or something happened to them.”

Hill was a well-known painter in her day—her iconic western landscapes were exhibited at four different world’s fairs, among other locations—and today her voluminous collection of landscapes, still lifes, and portraits of Native Americans belongs to University of Puget Sound. Lesser known is Hill the writer. Prolific under the most rustic circumstances, she scribbled thousands of pages while resting in tents, in boarding houses, on trains—whenever she could catch a moment after hiking all day with four young adolescents in tow. Often, she reflected on the spectacular beauty around her, as in this 1895 entry from a Mount Rainier trip: