On a recent afternoon in a Greek History classroom, 19 students found themselves in the brutal winter of 405 BCE.

According to the scripts in their hands, they were oligarchs, generals, landowners, citizens, women, and slaves, all locked within the besieged walls of Athens.

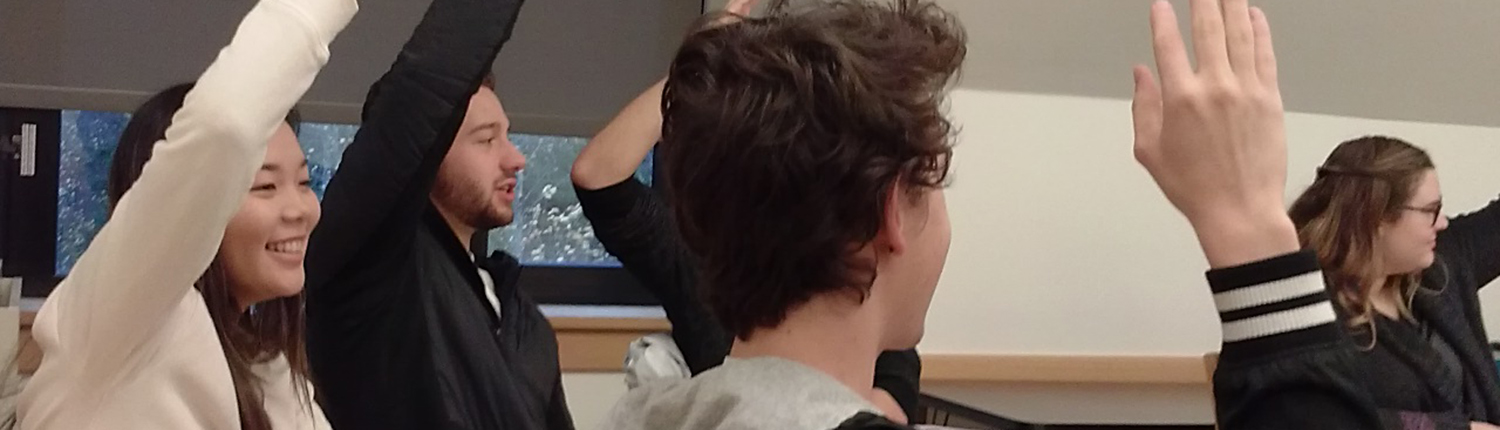

There was little food left, and the Athenians faced a choice: Surrender to the tyrannical Spartans and risk becoming slaves, or stand fast and protect the democracy of their great city, at risk of starvation. Each student in character strode, trotted, or ambled to the front of the assembly to argue their case. In the heat of the debate, an assassination attempt was made—and failed miserably.

The class was engaged in Reacting to the Past, the innovative learning technique pioneered by Barnard College professor Mark Carnes in the late 1990s, which includes 18 elaborate games related to a period of history. Each student plays a historical figure and has to argue for the principles held by their character. Over the course of several weeks, the students read extensively (in this case, Plato, Plutarch, Thucydides), write and deliver speeches, strategize with their allies, and try to confound their opponents.

Back in the Greek History classroom, things were not going well. Within 40 minutes, 15 Athenians were dead. Classics Professor Eric Orlin’s Starvation Lottery, which required all characters to pluck their fate from his terracotta urn, had taken its toll. And unbeknownst to those in the room, their dead comrades had reincarnated as Spartans, and were gathering next door to plot a siege.

Ten minutes later, the last four Athenians, refusing to surrender, had starved to death—a surprising outcome. “It wasn’t what should have happened,” Eric says. “Their goal was to become rulers of Athens with Sparta’s support.”

Eric’s surprise was typical of what can happen in Reacting to the Past. Whatever takes place at any time is entirely up to the students. “They have to imagine themselves in the shoes of somebody else and react to a situation,” Eric says. “Instead of just absorbing material [as in a lecture], they absorb a certain amount and then push back. This forces them to use their creative thinking skills.”

Tatyana Dunn ’20, who played the rich aristocrat Xenophon, said what’s really tough is being a character with values different than your own. “Xenophon was a sexist male; one of his points was to not let women be part of the Assembly. So it was hard to argue for that,” she says. Nonetheless, “It really helped with my argumentation skills, because you really had to stand up for yourself.”

Over four more classes, the students, in character, debated and voted on issues such as: Should foreigners be allowed to vote? Should Athens demand tributes from other city-states? And should Athens be governed by an assembly or a council?

Laure Mounts ’20, playing the character of Diogenes, a homeless philosopher, was fully into it. “Are you assembly members dull?” she spat in one session, as she criticized a classmate seeking to lead the tribute mission. Amid heckling, she told a tale about men laughing at an ass, closing with, “And so do the asses laugh at men.”

Not surprisingly, the game can get a little emotional. The language may be blunt. Students may betray their friends. Inevitably, one team of allies loses. That can feel like failure. For that reason, Eric says, holding a final “debriefing” class is essential.

“We talk about: Why did this team win? Did they just have more advantages? Did their players work harder?” he says. “That debriefing becomes the moment when students get to see the big picture, and what happened, and why. It helps them go back to being students.”

As for grading, papers and presentations count. “The thing I really look for in students is playing their role as best they can. How strongly can you make the arguments that your character would plausibly have made?”

Winning and losing does not count, Eric emphasizes. After all, some characters get dealt the right cards in life and some don’t. “That’s one of the things this game emulates,” he says. “Life’s not fair.”