In the last year, Kurtis Baute has spent 14 hours in a homemade biodome, run a marathon to demonstrate the timeline of human history, gone 24 hours without touching plastic, and measured the size of the Earth with two sticks and a bike.

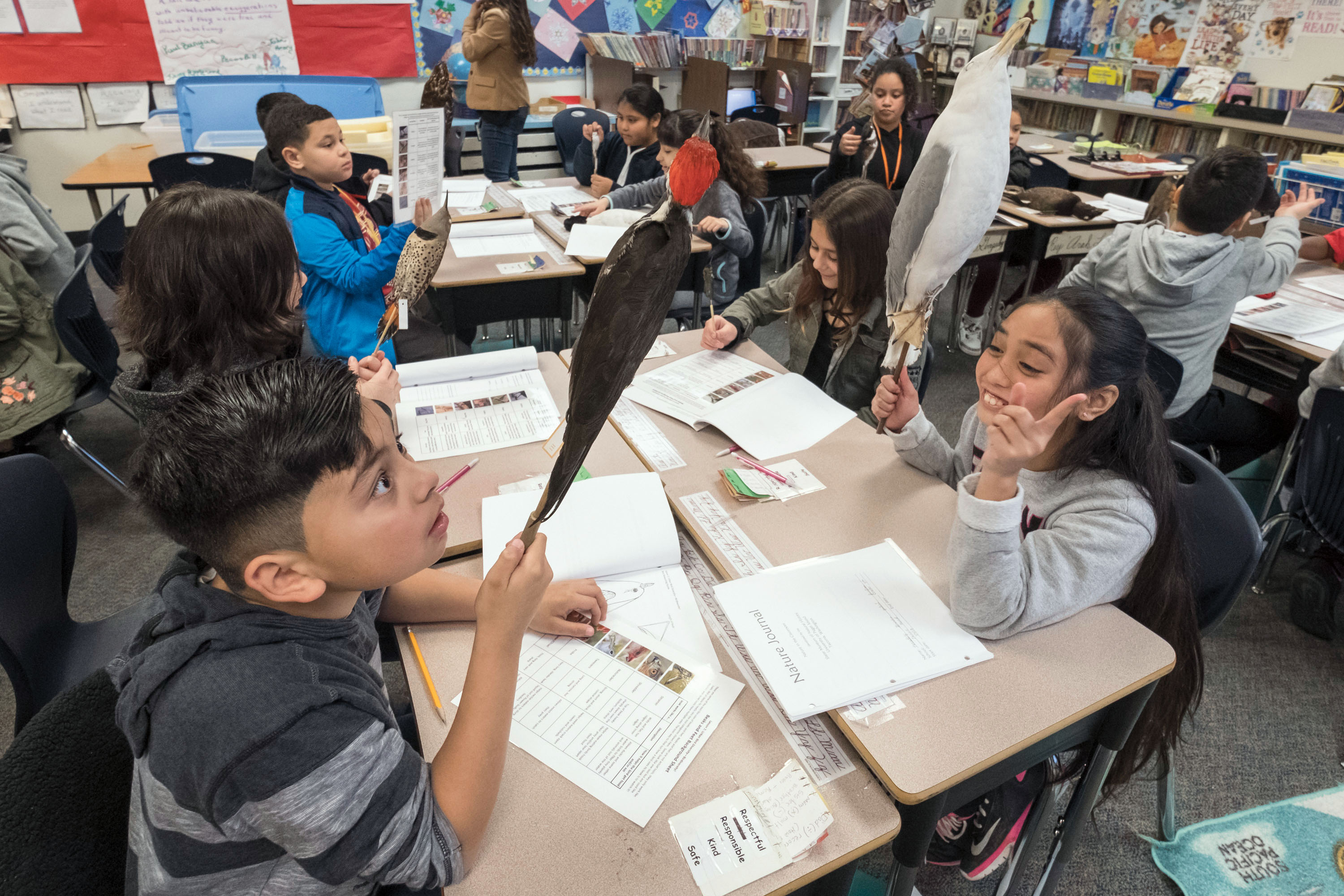

All in the name of science. The Vancouver-based educator has a zeal for the scientific method and a burning desire to make the principles he loves relatable.

Enter YouTube. After years of uploading science videos for fun, Kurtis quit his job and became a YouTuber full time. It was a gamble. He had 256 subscribers on his channel at the time and no guarantee that the world wanted more content from a former grade-school science teacher. Then a couple of his videos of science experiments and demonstrations went viral, getting picked up by news outlets including BBC and CBC News, and eventually—like a papier-mache volcano at a seventh-grade science fair—Kurtis’ channel exploded. In March, one of his videos hit a million views, and at last count, his subscribers numbered more than 100,000.

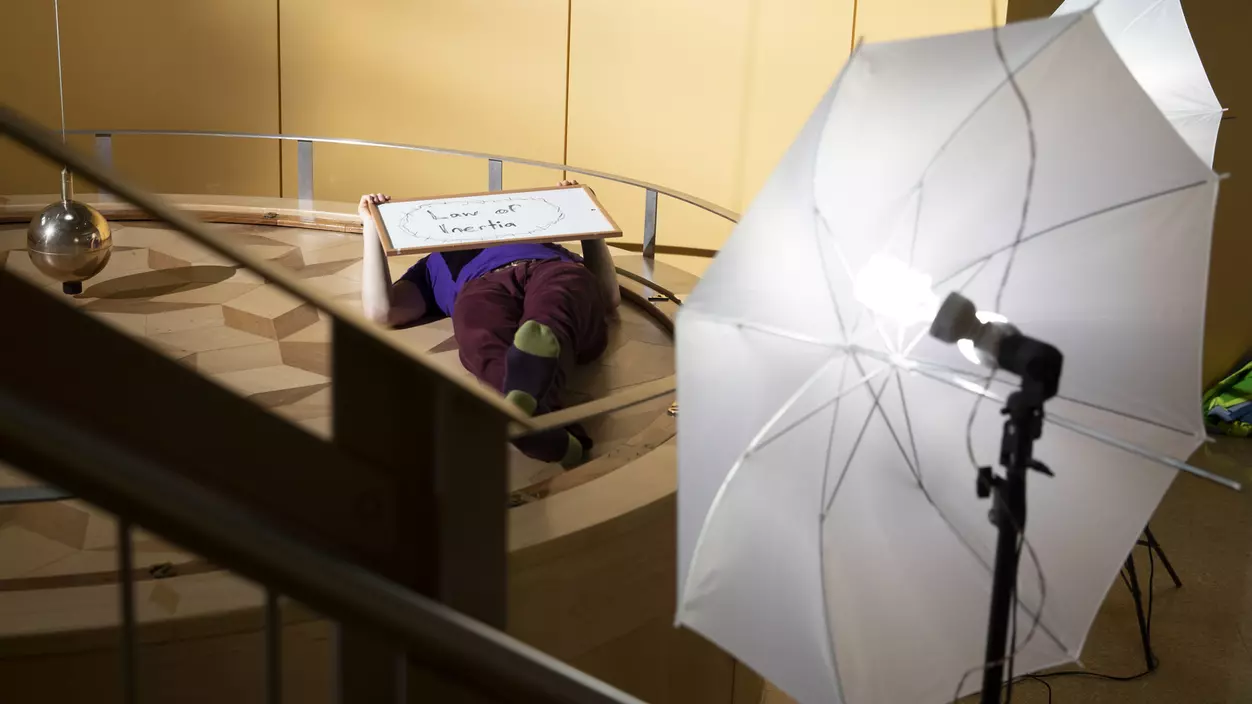

For his latest project, Kurtis honed in on the Foucault pendulum in Harned Hall. He camped out there for 28 hours straight to make a time-lapse video that showed the entire rotation of the Earth. We chatted the morning the video, Watch the World Turn, went live.