Puget Sound profs and students explore the city’s anti-Chinese violence of the late 1800s—and its legacy today.

Tacoma had fewer than 1,000 residents in 1876, when Tak Nam and Lum May opened their mercantile shop, Sam Hing Co., on what is now Commerce Street at 9th Avenue.

The business thrived selling medicines, teas, rice, and other goods, and the shopkeepers had a good relationship with Tacoma’s city leaders.

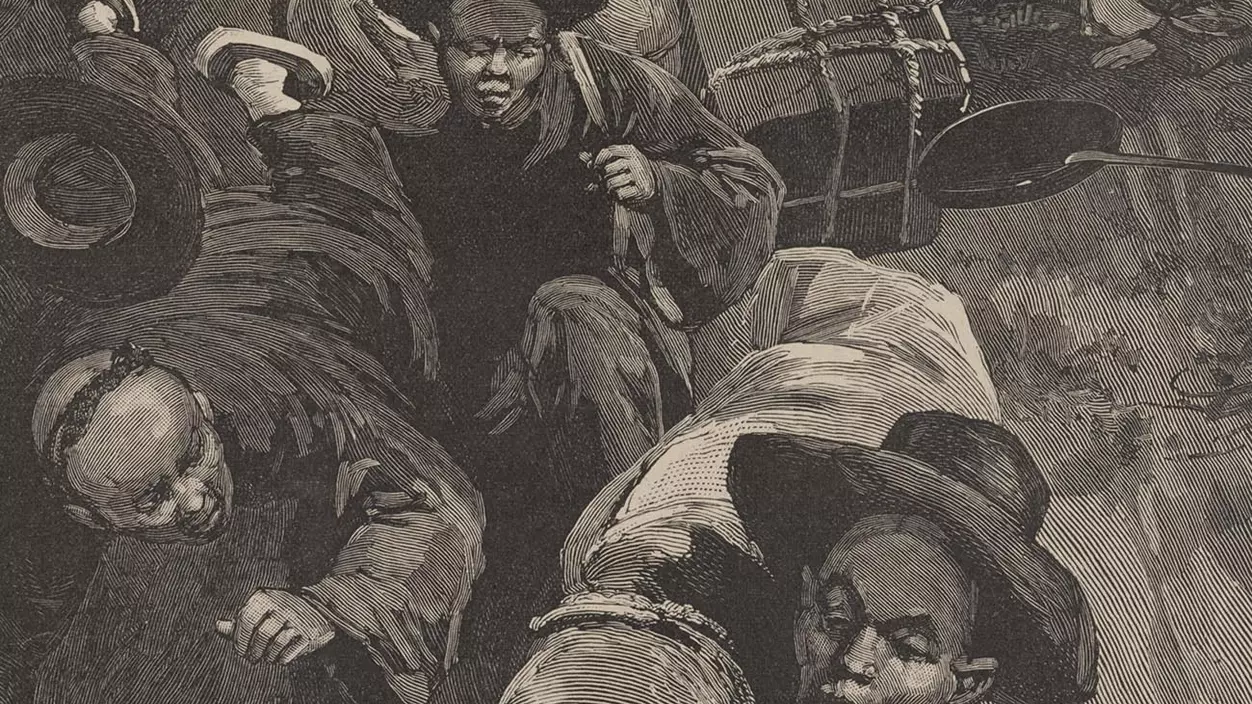

Nine years later, the two merchants—along with 200 other Chinese residents—were driven out of the city at gunpoint by an angry mob, their homes and businesses destroyed. The expulsion of Tacoma’s Chinese residents in 1885 was part of a pattern of anti-Chinese violence that permeated the West Coast in the latter part of the 19th century, but its story is not well known in Tacoma, and its lasting effects are not obvious. Puget Sound Associate Professor of History Andrew Gomez and Asian studies instructor Lotus Perry are working to change that.

Gomez teaches several classes in which students research the events of 1885; the students have built a website using their research, The Tacoma Method (tacomamethod.com), to spread the story to a larger audience. Perry brings awareness of the expulsion into her classes and into the community, as well, as a board member of the Chinese Reconciliation Project Foundation. “A lot of people did not know about this piece of history,” she says. “A lot of people did not realize that anti-Asian racism has gone all the way back to the mid-19th century.”

In the 1800s, multiple wars engulfed China, causing widespread poverty, hunger, and unbearable living conditions.

When gold was discovered in California in 1848, Chinese shipping companies began to sell the myth of the gold rush with ads promising “big pay, large houses, and food and clothing of the finest description” for workers making the journey across the Pacific. Starving and homeless people fled China in droves. Tak Nam and Lum May were among the thousands who came to the U.S.