When people walk into the Jenkins Johnson Gallery, a few steps from the bustle of San Francisco’s Union Square, they enter an eclectic space.

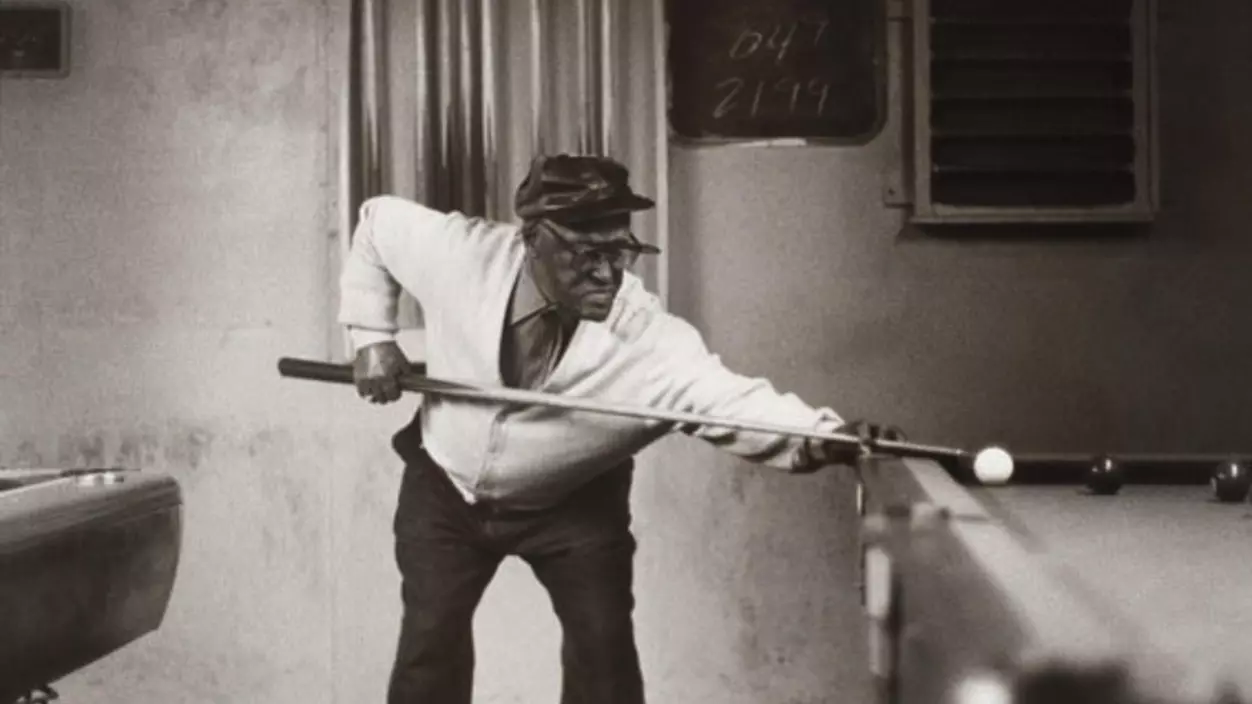

There is sculpture, mixed media, playful photo-realism, and the breathtaking photography of the late Gordon Parks. Some of the works are political, confronting the viewer with unexpected juxtapositions, like a Muslim woman wearing an Hermès scarf as a veil. Others reflect the joy and sensuality of summer. They all come together seamlessly through the discerning eye of Karen Jenkins-Johnson ’82.

For 25 years, Karen has built an international reputation as a gallerist committed to elevating artists of color—artists who had long been shut out of the art world. In a realm that she finds is often dominated by white male gatekeepers, she has gotten the work of diverse artists into museums, private collections, and other places where it had never been seen before.

“In one way, gallery work is advocacy,” she says. “I see the pathway to feature artists on a bigger scale, beyond the limitations that others have put on them. One of the things my parents taught me is that only I can allow others to put limitations on me. I don’t allow that, and I don’t allow others to put limitations on my artists.”

The youngest of William K. and Fannie Mae Jenkins’ five children, Karen grew up in Portland, and was the first of her siblings to go to college. Her father, who served in the Korean War and was the first black officer to lead Marine troops in combat, was a tough and practical man who taught his children a strong sense of self-sufficiency. Karen chose Puget Sound for its academic reputation and its relative closeness to home, among other factors. She chose a business major and joined the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority, where she was only the second African American member of the campus chapter.

It was Puget Sound’s core curriculum that had the greatest impact on Karen’s career path. In art history she studied five centuries of paintings, from the Renaissance to the early 1900s. “I learned how art came to be, the history of those times, the influence of the church and wealthy benefactors,” she says. “It gave me an intellectual basis for how to view the world.” The next summer, staying with family in Washington, D.C., while working a summer job, she spent her free hours exploring museums. The National Gallery had an exhibit of post-Impressionists: Manet, Monet, and others she had studied. Seeing the paintings in person made Karen’s spirit take flight. Still, even though her heart told her to study art history, “I didn’t see any clear, solid path there to being able to pay my rent.” She stuck to her business major.