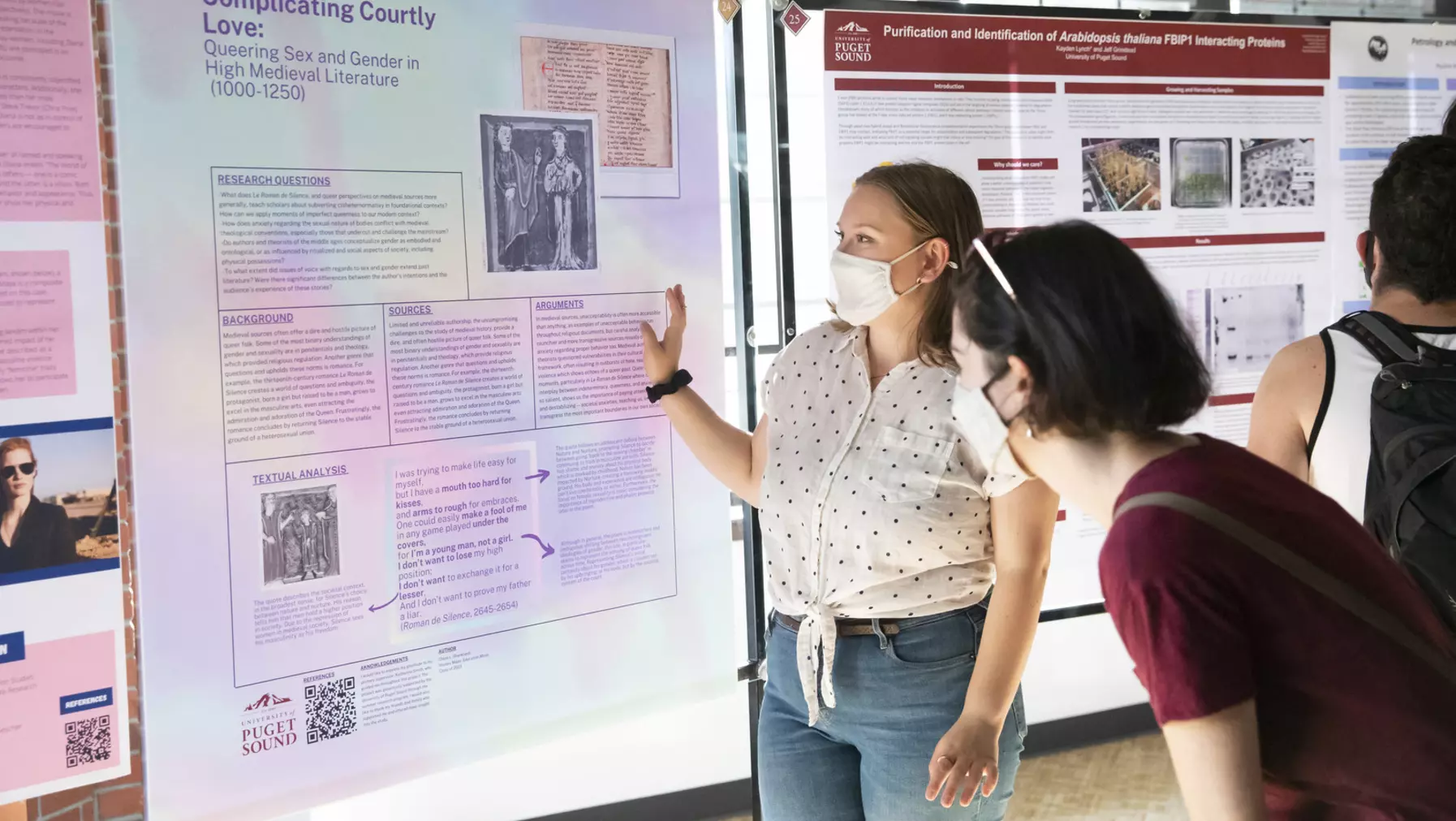

Chloe Shankland ’23 searches for queer representation in high medieval literature

Books and movies often portray medieval Europe as a highly regimented, theologically conservative society marked by strict gender roles and a total absence of queer people, but according to history major Chloe Shankland ’23, that view isn’t accurate. While few sources exist, literature from the period hints at a vibrant world of nonheteronormative art and culture.

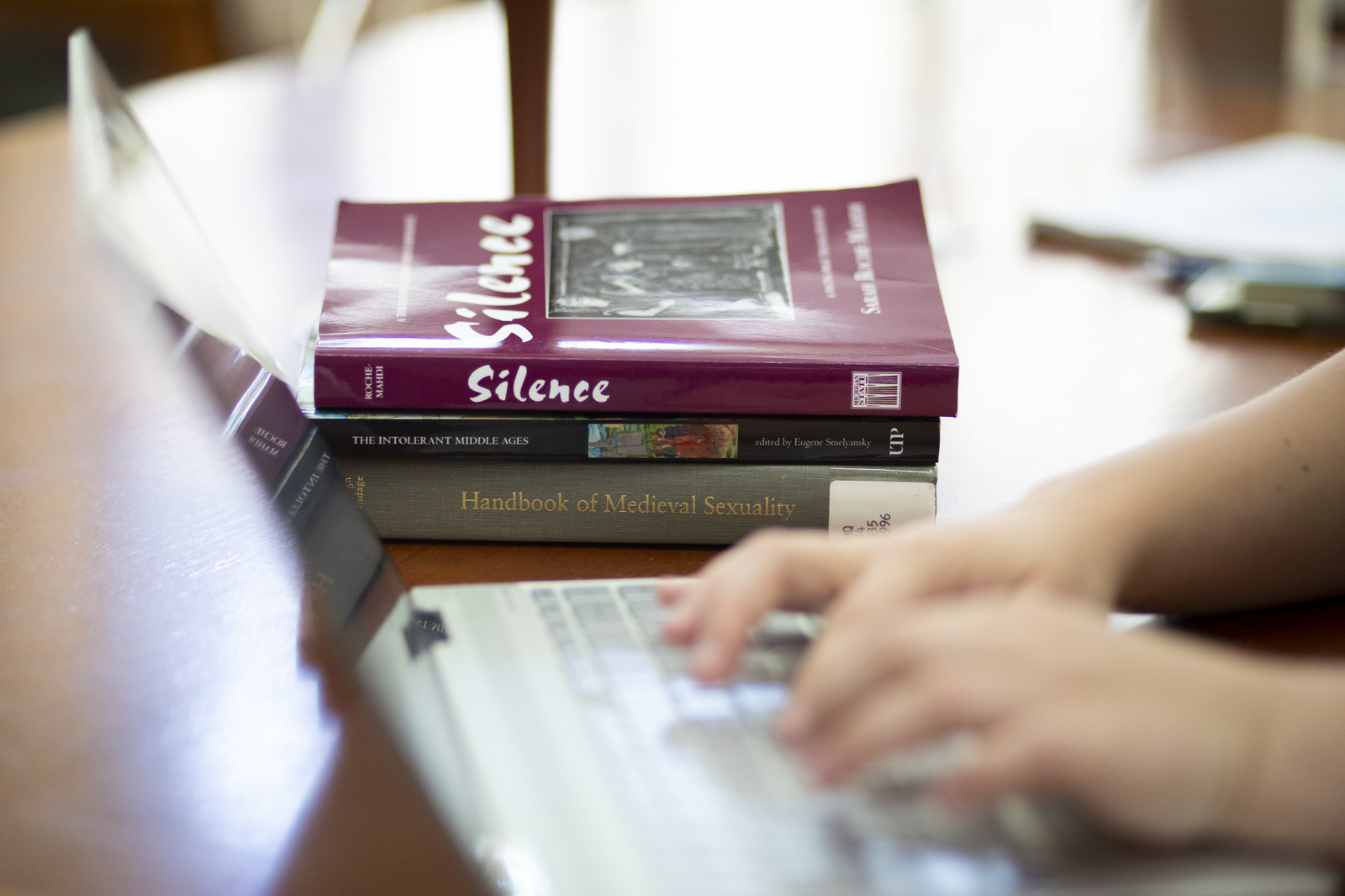

Shankland worked with her advisor, Professor of History Katherine Smith, to examine poems, legal documents, and church records from 1000 to 1250 A.D. in search of references to queer identities and fluid gender roles.

“It’s been fascinating to see how writers were challenging their society’s expectations of gender and sexuality,” Shankland says. “A lot of modern scholarship has erased queer and trans narratives in medieval source material, but the evidence is there if you look hard enough.”