A new book by Rachel S. Gross '08 interrogates the history of outdoor brands and how they came to define the American way of exploring nature.

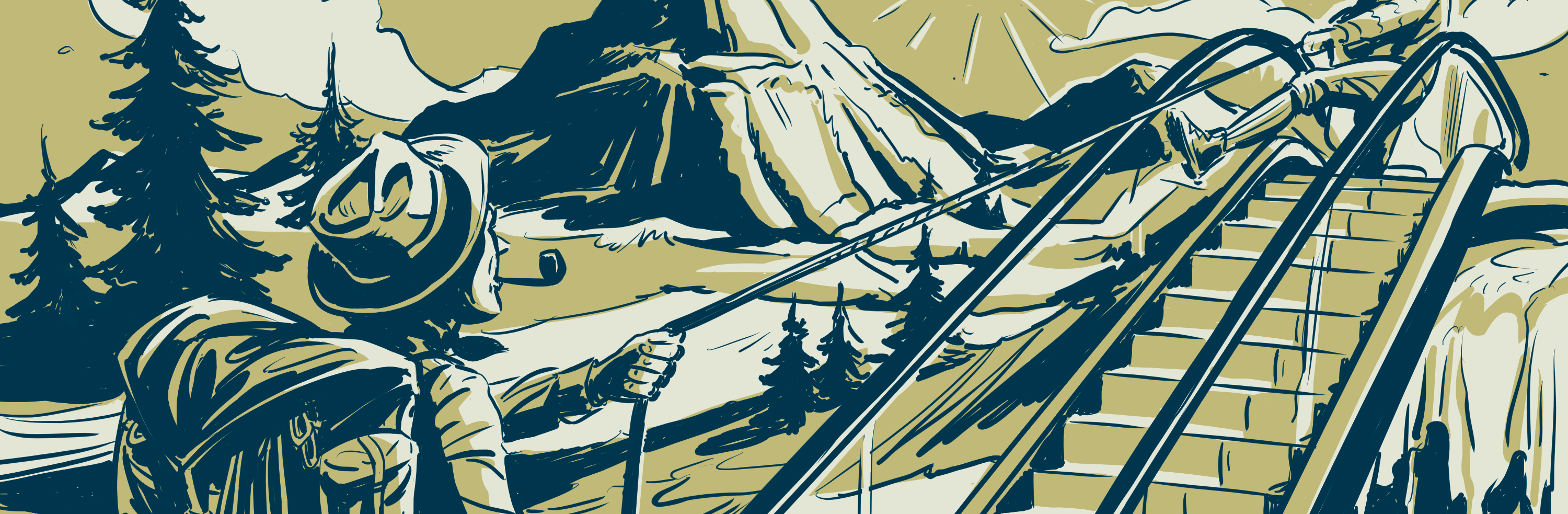

Rachel Gross ’08 notices those logos on your clothing. Your Patagonia rain jacket, REI hiking pants, and Chaco sandals are more than just pieces of equipment to her. Gross, assistant professor of history at the University of Colorado, Denver, is an outdoor gear historian who studies the business and culture of brands. Her new book, Shopping All the Way to the Woods: How the Outdoor Industry Sold Nature to America (Yale University Press, 2024), chronicles the history of outdoor retailers and explores how consumers came to associate buying gear with the notion of escaping into nature. We asked her about the new book and its origins at Puget Sound. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

A couple of different places. As a student at Puget Sound, I did a summer research project expanding on work I did in History 200 with Nancy Bristow. It was on the history of women’s park ranger uniforms in Yosemite in the 19th and 20th centuries. In many ways, this book is a very expanded version of the project I started in that class. The other answer is that after I graduated from Puget Sound, I had a Watson Fellowship and I went hut-to-hut hiking in places like Switzerland, India, and Chile, pursuing this question of how different cultures understand the meaning of wilderness and how that shows up in the recreational spaces that they offer to tourists. On that trip I encountered a lot of people who needed to tell me how I was packing the wrong stuff, wearing the wrong backpack, and doing things not correctly. When I returned to the U.S. and grad school [at the University of Wisconsin-Madison], that was what I wanted to explore: to understand how this particularly American way of dressing for the outdoors, equipping ourselves for nature, came to be.

How did your Puget Sound experience shape you as a historian?

History 200 was a methods class—basically how to become a historian, how to read relevant historiography, how to understand what arguments you’re making that are different from those, and then how to ask good questions of primary and secondary documents. I reviewed a book on national park history for that class. I delved into the available online resources, primary documents related to Yosemite’s past. And then in the summer research project with Doug Sackman, I got to go to the Yosemite research library within the park boundaries itself. That was really what opened my eyes to the possibilities of being a historian. I realized both how much I love the process of research and uncovering new stories and archives that people hadn’t paid attention to before, and how much I enjoyed sharing that with a broader audience.

What was the research process for the book?

There was no set archive or library where all this information was located. So I cold-called a whole bunch of outdoor companies to say, “Do you have archives and can I come look at them?” Most places said no, but a few said yes—letting me into either formal and beautifully cataloged archives or, you know, bins in a closet, or stacks of paper in a back room somewhere. I went through those archival treasures in more than 15 states as a way of uncovering the story of the industry and understanding the relationship between the companies and the consumers who bought from them.

Tell me more about the response you got from outdoor companies.

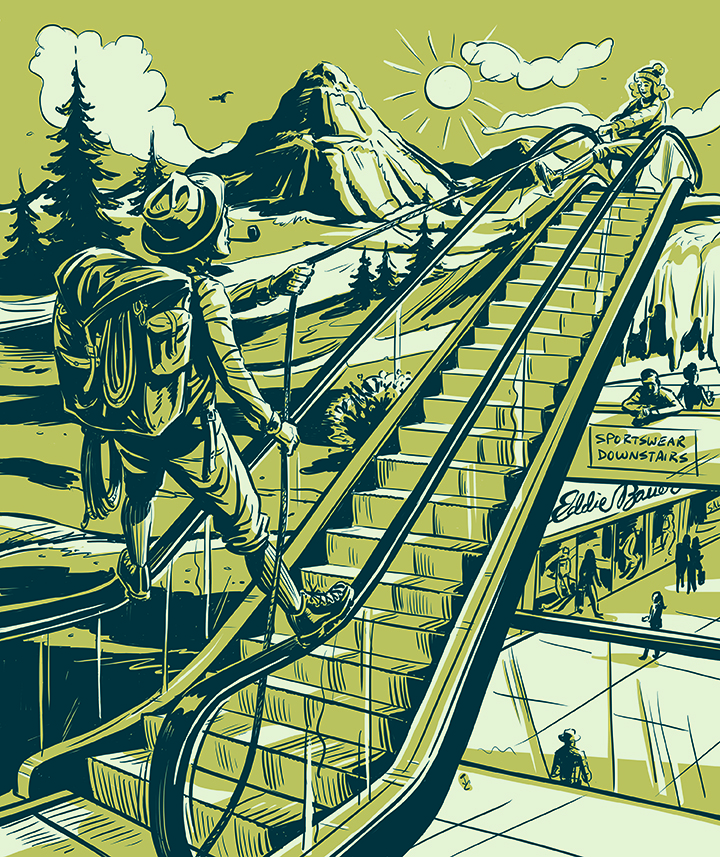

A lot of companies, when I started this project 13 years ago, didn’t have formal archives or collections. So the “no” was not just “We’re going to protect our story” or “We don’t give access to outside researchers,” which is the case for some privately held companies. A good example of that is L.L. Bean, which has an archive but publishes its own histories and doesn’t want to let other folks in. But a lot of other places just hadn’t done the collecting work. They hadn’t seen the history of their companies as valuable. The companies that did say yes—Eddie Bauer is a good example—had a formal archive and archivist position, a gear library with historical materials and their old jackets that people who worked in the design department could check out. I also had a lot of fun looking at the closet at Adventure 16’s headquarters outside of San Diego, where the CEO welcomed me in and let me look at things like newsletters they had sent out to customers in the 1970s and 1980s. These days, you can go to Utah State University, to the Outdoor Recreation Archive. But none of that existed when I started this project, and I hope that my work can help highlight the ways that this history of business can be valuable, and lead to more people preserving their past.

The origins of the American outdoor industry, you write, are full of paradoxes. How does this alter the behavior of consumers?

I mean, gear is supposed to function, right? And one of the important things on people’s list is, Is it going to keep me warm or dry or safe? Am I going to die if I go up a mountain wearing this jacket or using this tent? I think that’s a crucial question and ideally the starting point for all of us if we’re acquiring something new. But that’s not the only thing we’re thinking about. I certainly put myself in this category of a consumer with a varied set of interests—I’m interested in how warm or dry I am but also in the brand emblem that’s on my chest or my shoulder. And I think the reason that consumers show this affinity for particular brands is that brands have cultivated stories around what they represent—stories that go beyond functionality and speak not just to style but to expertise or belonging.

A large part of the book focuses on the military origins of brands like Eddie Bauer and L.L. Bean. Why is that history important?

Tracing the military origins, not just of products themselves but of the way of testing and asking questions about what works, is important because it shows how deeply tangled the outdoor industry is, with both national history and specifically with the military-industrial complex. The Vibram sole, for instance, has its origins during World War II. A lot of military technology became civilian wear in the decades that followed. I think one of the presumptions that consumers like me had was, “Ah, this product will allow me to escape from commercial life and give me an entry point into wild nature.” And this history of gear not only deconstructs that idea but also shows that the federal government and the military apparatuses had a really heavy hand in shaping what we buy—and what we think we ought to buy.

How did writing this book make you rethink your relationship to the outdoor industry?

Part of doing this project over so many years meant that as I grew older alongside of it, what I needed shifted. Older folks can carry less weight because their backs hurt more, for instance. I actually think that the biggest lesson for me has been that almost everything that I think I need, I don’t. In other words, the starting point for me was that the acquisition of goods is going to help me buy my way into an identity and a sense of belonging. What I’ve seen is that generations of Americans dating back to the 19th century have thought that if they had access to a certain kind of commercial goods, they would be a part of the culture that they wanted to be. And for the most part, they didn’t need those specialized goods. So this project has reminded me that the impulse I have to get more stuff—because it’s cool, because it works really well—isn’t always necessary. So I actually buy less stuff now.

At the end of the book, you highlight some groups working to change the outdoors industry. Where would you like to see the outdoor industry go in the future?

One of the important groups that I talk about is Natives Outdoors. It’s a really interesting organization that has had some collaborations with gear companies to design new outdoor products. But rather than appropriating Native or Native-inspired design, they’ve included Native artists and designers in that work. I think that’s crucial, because the entire book traces the origins of the outdoor industry and the expertise of Native Americans, particularly Native American women who made buckskin suits for white outdoorsmen. Acknowledging that history is important, but in many ways, figuring out what we do with that history is far more complicated. I think Natives Outdoors is doing a version of that. It doesn’t right the wrongs of decades of erasure or appropriation, but it does pave the way for that new outdoor aesthetic and honor a different past than the imagined heritage of Eddie Bauer of the 1990s, for instance.

You're one of the judges for the Innovation Awards at the gear industry’s Outdoor Retailer trade show. What are some cool new products we may see soon?

The award winner from last year was WoolAid bandages, which are essentially BandAids made from wool. When I saw that it’s possible to make a product that’s going to protect my wound while it heals—that’s also made out of a natural fiber—I couldn’t believe no one had ever thought of it. Other products include skis that aren’t made from petrochemicals, and products with return labels so that if you lose your glove, people can scan a QR code and return it to you. Gear innovation is less about “Oh, this jacket is warmer than ever” and more about “What broader impacts can it have on the environment and how do we lessen the footprint of the industry as a whole?”

What do you hope the casual outdoors person takes away from this book?

I hope it helps people shed some of the presumptions that we have about the right way to participate in the outdoors. Or that one version of dressing as an outdoors person is the one that’s going to make you fit in. The reason that matters is because it can pave the way for a broader sense of inclusion for more people and in more places doing a range of activities that don’t have to be at the pinnacle of a sport to be important or valuable to them in their lives. I think the other takeaway is that we have to think carefully about what we acquire, given the broader impact that we know the consumption of goods has on our environment. And so if each one of us critically examines our own habits—at the same time that outdoor companies are continuing to pursue their different versions of sustainable business—we can all approach our habits from a more critical place.

Trailblazers

In her book, Shopping All the Way to the Woods, Rachel Gross ’08 highlights the lack of diversity in the outdoor industry, but points to promising trends for the future. Here are five companies working to make the outdoors a more inclusive space.

1. Outdoor Afro

“Outdoor Afro celebrates and inspires Black connections and leadership in nature,” the nonprofit organization writes on its website. In addition to hosting outdoor education and conservation events, Outdoor Afro has partnered with REI to design a line of camping gear and clothing, in addition to collaborations with Keen, Smartwool, and other companies.

2. NativesOutdoors

NativesOutdoors was founded to elevate Native people and stories in the outdoors and address the lack of representation of Indigenous people in the outdoor industry. NativesOutdoors has partnered with Eddie Bauer to confront Indigenous appropriation in gear and to elevate Native artists and communities in the outdoor industry.

3. Blackpackers

Blackpackers “addresses the gap in representation and provides gear and lessons for how to pack for a backpacking trip,” Gross writes in her book. The nonprofit also provides outdoor education and trips at a free or subsidized cost and works to create new career paths in the industry.

4. The Venture Out

Project Venture Out leads backpacking and wilderness trips for the queer and transgender community. It also offers inclusivity workshops as well as hiking, backpacking, canoeing, and other kinds of outdoor trips. Venture Out has worked with REI, Eddie Bauer, Marmot, and other companies.

5. Fat Girls Hiking

“Fat Girls Hiking creates a community for safe spaces and more access with online advice on gear that fits,” Gross writes in her book. The group aims “to create a space where fat and marginalized folks can come together in community,” they write, in order to create a more body-inclusive vision of the outdoors. Fat Girls Hiking hosts events and has chapters across the United States.