Your research focuses on cell biology and the mechanism behind cancer. What drew you to that area of study?

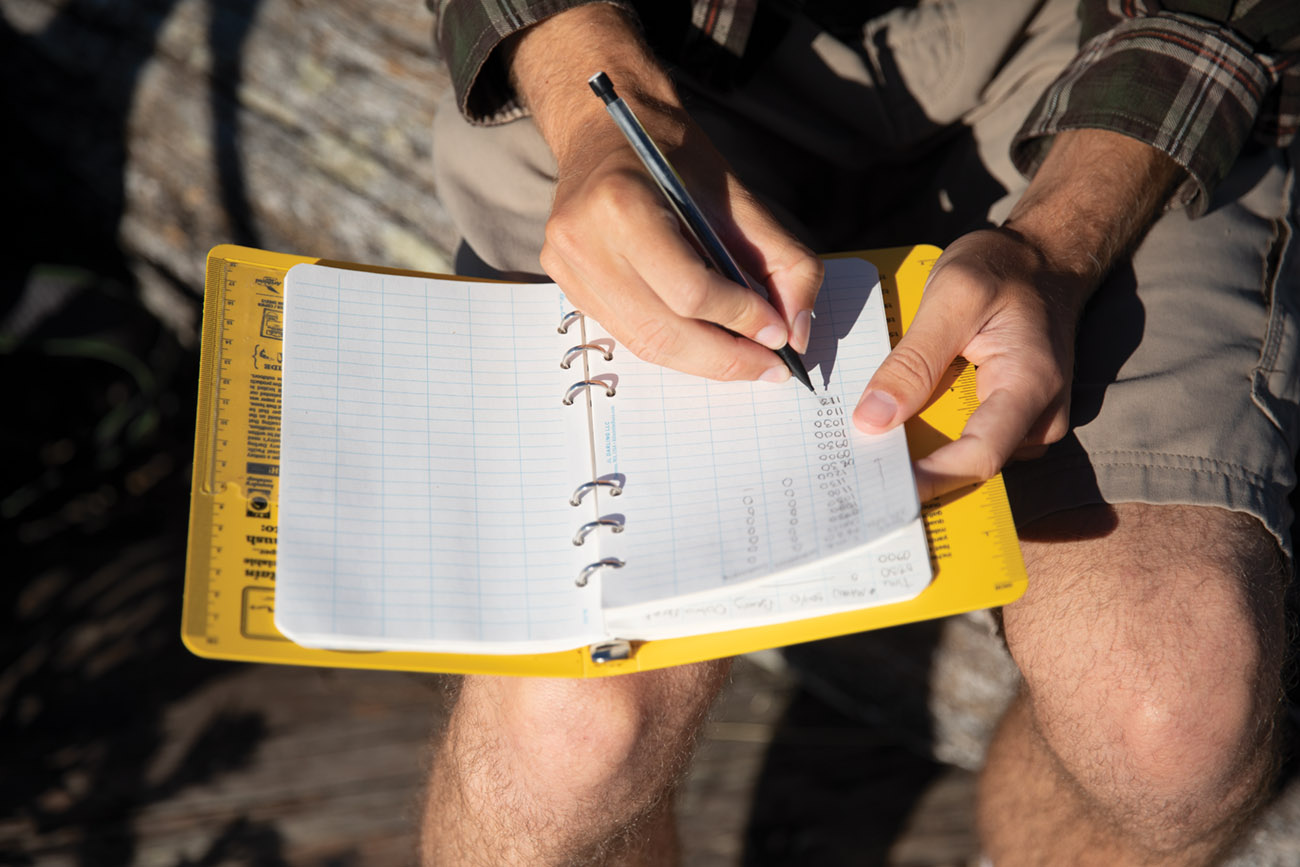

In my lab, we work with fruit flies, which I never imagined I would do. I started out working as a technician in a lab that was looking for genetic mutations in people who were more susceptible to Neisseria, a family of bacteria that causes meningitis and gonorrhea. It felt very important to be working with human subjects, but it turns out that you can’t control humans, which makes them hard to study. So, I moved into working with cells in tissue culture obtained from mice and humans, which included researching skin cancer in people who had a genetic predisposition for it. When I came to Seattle, I interviewed with someone who was doing research with fruit flies. At first, I scoffed at it, because a fruit fly is so simple compared to an organism like a human. But fruit flies have been used as a genetic system for more than a hundred years, and I came to realize how useful they are in understanding how cancer forms, because you can control every variable. You control the matings, you control the environment, you can take genes, add some, take some out, and change their sequence—and you can learn a lot that way.

You have a 2023 book called Getting to Know Your Cells. What inspired you to write it?

The book was born out of a need I had. A lot of cell biology textbooks start out very chemistry-heavy, because you have to know all of the tools first—and that can be intimidating. By the time we get to cells and all the cool things that cells do, we’re halfway through the semester and I’ve lost some of my students. An analogy I’ve used many times is that I don’t know how a car works, and if I had to just sit there and memorize every piece of a car before I knew what a car looked like, I don’t think I’d follow through on that. But if I saw a car, I’d be like, “Oh, I want to know how that works.” So that’s what I did. I decided I needed less of a textbook and more of a field guide, so that we can sell students on how fascinating cells are without beating them over the head with complex chemistry.

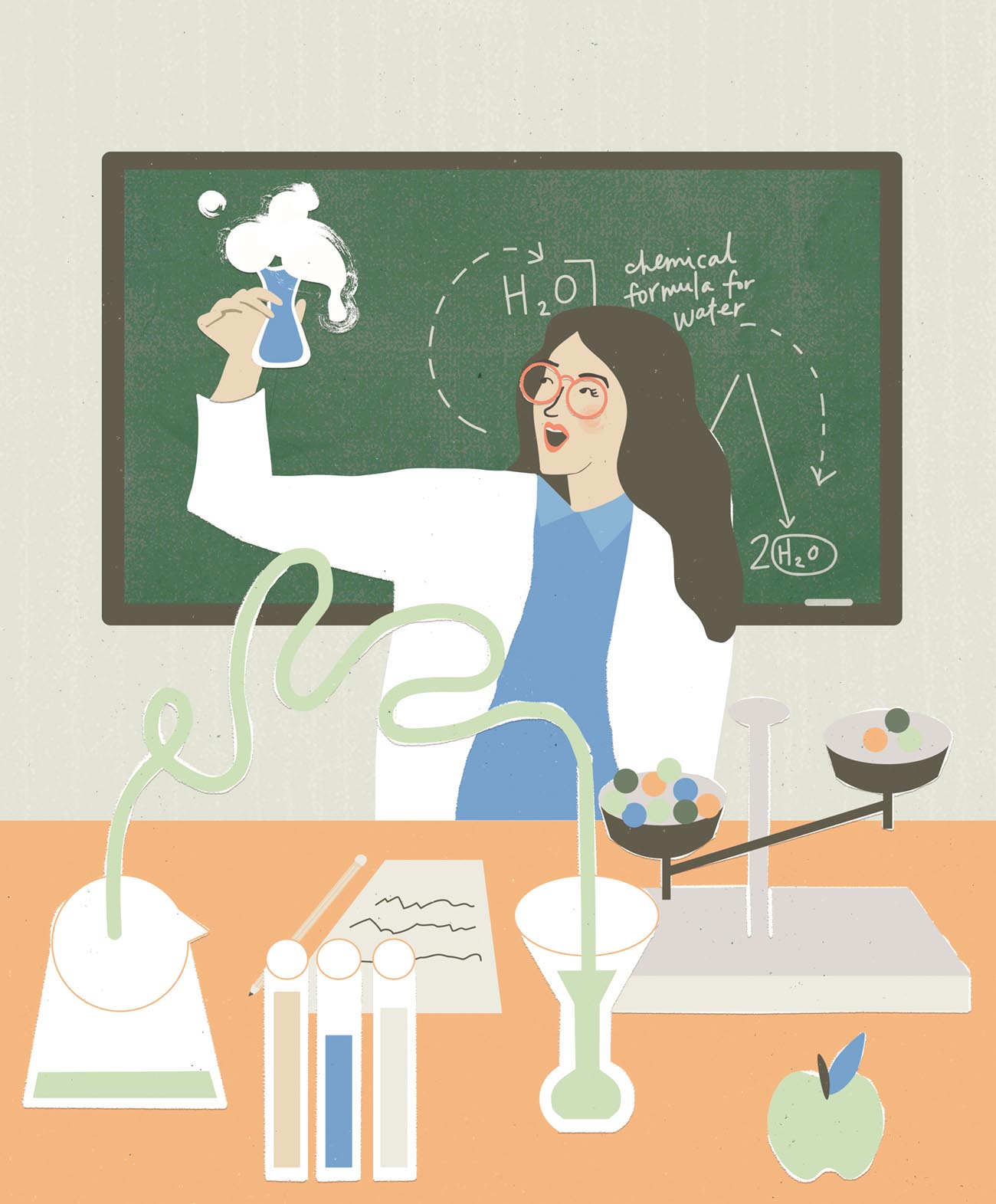

The book is illustrated by a Puget Sound alumna, Maria Jost ’05. How did that collaboration come about?

Working with Maria was probably the most fun part of doing the book. She graduated shortly after I started here, and she’s always been on my radar. I’m a big fan of her art. She mostly does botanical drawings, and she’s done some public installations around Tacoma. She’s also an instructor at the Science and Math Institute here in Tacoma. I reached out to ask if she would illustrate the book, and she agreed. We met once a month for a year. Meeting with her and trying to tell her what I wanted was fascinating. I’d give her horrible, hand-drawn sketches and she’d turn them into these beautiful images.

What do you hope students get out of your classes?

A love of learning, honestly. My goal is to have students realize that teachers aren’t just graders and assessors who throw assignments at them. Teachers can model how to dive into a subject and be challenged by it, show them how to work through it and succeed. I think sometimes my students get a little frustrated with me, because I will let them struggle a little bit, especially in my senior capstone course. It’s all hard-core scientific papers. I tell them in week one, “You have to be comfortable with all that you don’t know, and that’s OK.”