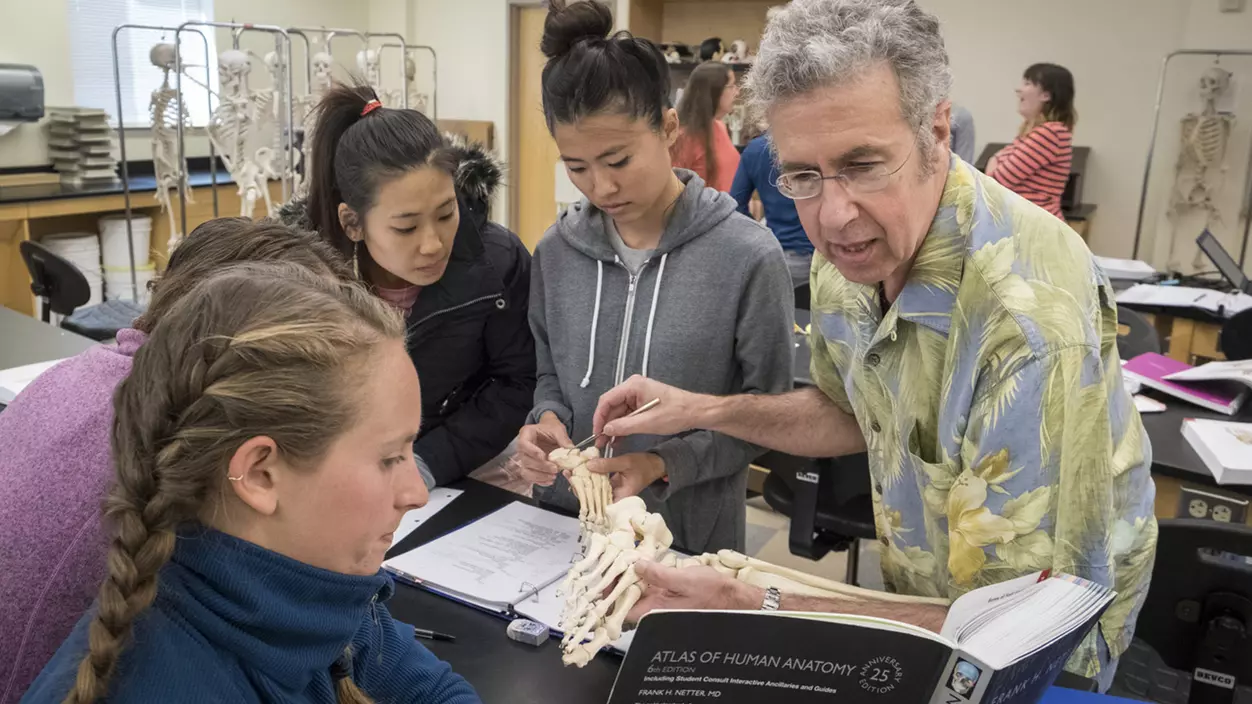

On our way to the teaching clinic downstairs, which offers pro-bono physical therapy to people from the local community, Allen continues to greet, by name, everyone we pass. He says things like, “I’m so glad you’re here!” and “It was so good to see you, really!” You can tell he means it. Students and faculty are still adjusting to seeing one another in person again—he’s proud of how they were able to adapt during COVID, but teaching clinical anatomy over Zoom, he says, was not ideal.

Allen has undertaken two dominant lines of research into pain. The chronic pain that he studies ranges from the exhausting, full-body pain of fibromyalgia to phantom limb pain, where a person experiences painful sensations in amputated limbs that no longer exist. Evolutionarily, pain is a valuable danger signal. But if it persists past the point of being helpful, its source can move from the body tissue into the nervous system and construct an experience of pain that the mind, not the body, perceives and suffers.

“For 30 years,” Allen says, “the pain science field has known what the physical therapy profession has only begun to embrace in the last decade—that pain is a phenomenon of the mind.” Allen raises his hand. “It’s not your hand that hurts, it’s your awareness of it.”

RELATED: Roger Allen: A Little Help From My Grad Students

From 1996–2009, Allen focused on something called neurovascular innervation mapping. He and his research team realized that a host of puzzling symptoms were caused by a pattern of nerve innervation (stimulation) to blood vessels, and that the current understanding of the peripheral nervous system had never adequately mapped those patterns.

Allen repeatedly credits his collaborations with students for igniting and nurturing these sparks of insight. Most of his research has involved doctoral physical therapy students and undergraduate neuroscience interns. He’s especially proud that more than 90 of his students have presented their work nationally or internationally or have published work in peer-reviewed journals.

“In graduate classes, students’ thought processes about what’s possible are still fairly naïve, so they often come up with left-field questions,” Allen explains. “But, if you know enough about the field, you can see how those questions might fit into the big picture. It can get really interesting.”

Allen’s more recent work—which stemmed from a grad student’s question in one of his classes—involves discovering and validating a 10-day delay between stressful events and increases in the perceived severity of pain in people who suffer from chronic pain. A person might have an argument with their spouse, or even just forget a friend’s birthday, and 10 days later might have a flare-up of their shoulder pain. The culprit: the hormone thyroxine, which after being released during times of stress is bound by blood proteins and—for reasons unknown—held inactive for 10 days. The next question is how to intervene and prevent the flare-up, but just knowing that a 10-day lag exists is beneficial to both health care providers and patients. Therapists can now help patients differentiate between stress-related pain increases and those potentially brought on by, say, physical therapy, and perhaps help them exercise some control over their suffering.

“Experiencing the sensation of pain is one thing, but how we suffer from it is a more complex matter,” Allen said in his Regester lecture. “The emotional experience associated with pain, or the actual suffering component, is intensified by uncertainty and fear. When we have a plausible explanation for why a flare may have occurred, much of the emotional impact is defused.” Emphasizing the complexity of individual pain helps students develop a true appreciation for how people are affected by the pathologies they study in class, says Danny McMillian, a faculty colleague in the School of Physical Therapy. “That awareness of the lived experience is critical in the development of holistic practitioners.”

Allen has also collaborated with doctoral students on research outside of chronic pain, including the discovery and application of what he calls a “curiously useful” treatment for vertigo based on electrical stimulation of the bottoms of the feet—another idea sparked by a student’s question in class.

We enter the clinic, where the main room hums with activity. One student encourages a patient ascending a flight of training stairs; another holds out an arm to steady a man on a wobbling balance board. A staged living space down the hall allows clients to safely practice activities like showering or getting off the couch.

It’s taken some time for Allen to get used to Weyerhaeuser, which opened in 2011—he never minded the pink portables with peeling paint that previously housed the PT/OT program, where he once had to choose between heating his office and the welfare of a family of raccoons living under the floor. But if the structures were temporary, the program could be as well. “The investment in the new building offered a sense of value and commitment to the programs,” he says. “There was no question we’d remain here.”

A few days before my deadline, I receive an email from Allen: “Quick update. I’ve elected to fully retire at the end of this academic year, after I teach my last clinical class in the spring.” He includes a picture of Loki, staring dolefully up at the camera.

Allen says he’s never had much trouble closing chapters, even one that defined so much of his life. But before this one ends, he hopes to teach his most engaging, relevant class yet. “There are recent developments in the field that will change medicine significantly, that will change the way students approach the profession,” he says. “I want to carry that into this last class.” Those developments involve a new approach to neuroplastic intervention—increasing the brain’s plasticity and responsiveness to remodeling. Combined with therapy, the approach could radically change the effectiveness of treatments to help restore movement, function, cognition, and communication. It also could reduce the suffering that comes with many disorders and chronic pain states.

Then it’s on to unlimited time with Loki and continuing guitar lessons. Allen has played for about 10 years but is now studying music theory with a jazz teacher—he wants to be able to improvise. It’s the hardest thing he’s ever tried to learn, “much harder than neuroscience.” And any day he’s able to work with his hands, to be creative and productive in some way, will be a good one.

When we talked last, he was waiting to receive a shipment of rosewood for a guitar he’s building by hand, clearly thrilled at the prospect. If there’s one thing that’s clear about Roger Allen, it’s that he doesn’t do anything halfway.